What Is Land Value Tax?

As flourishing economies drive up the value of land, standard property taxes fail to promote its optimal use, instead transferring most of the financial benefits to private landowners, to the detriment of the wider community. This dynamic worsens the housing crisis and encourages suburban sprawl, all while sapping the strength of the economy.

As communities grow, the structure of property taxes create incentives towards particular kinds of development and away from others. Standard property taxes are levied most heavily on the value of buildings and other human-made improvements that sit upon land, rather than the value of land itself.

This feeds two pernicious dynamics. First, it encourages speculative practices. Land owners may buy valuable land and keep it vacant, avoiding higher taxes by delaying any form of development, ultimately seeking to sell the land off at a higher price down the road. Land speculation withholds land from more productive uses, such as building housing or businesses that would benefit the community. It also forces further development to leap-frog speculatively held land and build outwards. This drives suburban sprawl that creates longer commutes and more congestion, consumes productive farmland and natural forests, and increases greenhouse gas emissions.

The second dynamic standard property taxes create is the private capture of collectively produced value, sapping away resources from further economic growth. Thriving urban areas generate immense value, but that value gets absorbed into rising land prices (and ultimately, rents) that benefit landowners, rather than cycling back into communities to feed a virtuous cycle of growth.

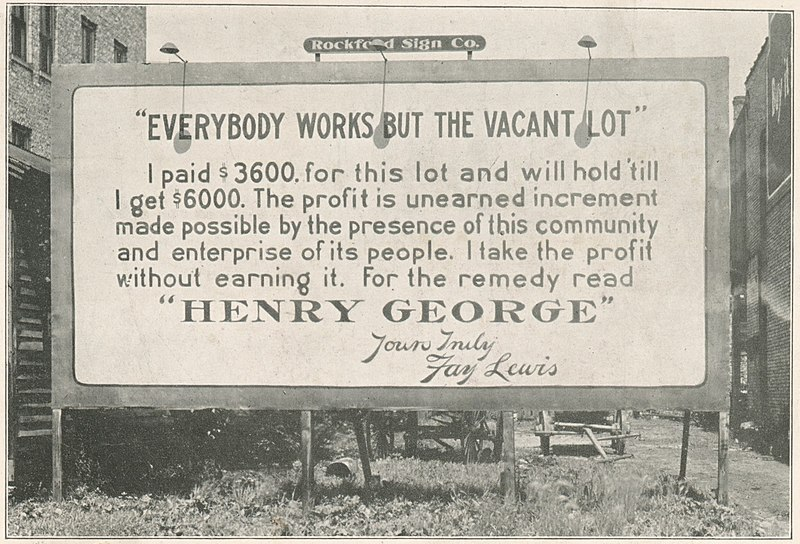

Private income generated from rising values on privately owned land has therefore been called “inefficient,” “rent-seeking,” “monopolistic,” “parasitic,” and even “the root of all inequality.” As a result, economists of all stripes — from classical economists like Adam Smith and Henry George, to modern ones like Milton Friedman and Joseph Stiglitz — agree that of all things to tax, land is best.

A land value tax (LVT) is a shift in the burden of property taxation. Rather than taxing the combined value of land, buildings, and improvements at one tax rate, it shifts the tax towards higher rates on the underlying value of the land itself.

Few other ideas in economic history have more bipartisan support in theory, with so little uptake in practice. Proponents argue that shifting the burden of property taxation towards land values would incentivize more productive uses of land, discouraging speculation while encouraging development.

Beyond immediate benefits — such as greater housing supply at lower costs, stronger business activity, and more resources cycling through communities — discouraging land speculation could have important long run effects. As speculators sell their land in response to higher taxes, the supply of urban land would rise and prices would fall, supporting further development.

The reasons LVT is so scarcely taken up appear to be largely administrative. Measuring the value of land — separate from the value of buildings and improvements — requires strong land valuation practices, teams of assessors, and high-quality data. Now that improvements in statistical methods are making valuation easier, might it finally be time to consider LVT?

Proposals differ on:

-

Whether to shift the full property tax burden onto land alone, or have a “split-rate tax” where land is taxed at a higher right while capital and improvements are taxed at a lower rate.

-

What tax rate should be placed on land value.

-

Whether an LVT should replace any other taxes, and if so, which.

Depending on its design, advocates argue that an LVT could:

-

More equitably distribute value created by rising land values.

-

Discourage land speculation.

-

Encourage urban development while reducing sprawl.

-

Provide a more efficient source of municipal tax revenue than any other tax.

Skeptics argue that LVTs:

-

Would be too difficult to administer in practice, especially where valuing and revaluing land is concerned.

-

Would fail due to complexity and confusion from such a change in property tax procedures.

-

Would cause overdevelopment.

-

Would create inefficiency by biasing land-use decisions.

What does the evidence say?

Effects of Land Value Tax on Growth

Where they’ve been applied, land value taxes generally promote building activity, reduce land speculation, and provide municipalities with an efficient source of funding for public services.

Econometric models predict that, if implemented at larger scales, replacing portions of existing taxes with LVT revenue would increase both GDP and social welfare, driven largely by replacing the distortion effects of other taxes.

Land value taxation promotes compact city growth, stimulating building activity while reducing urban sprawl. But urban development is not without costs, and LVTs may not always be the best tools for promoting development.

Economists across the spectrum agree that the present system of property taxation, with low tax rates on land value that allow property owners to capture most of the value of rising land prices, keeps the US economy from being as prosperous as it might be with higher land taxation.

In general, increases in land values come from three sources : the combination of land productivity and scarcity, the growth of adjacent communities, and the provision of public services. When tax rates on land are low, property owners privately capture a large share of these collectively produced increases in land value.

LVT advocates argue that value created by nature, public services, or the growth of communities should be shared by all, and not captured by property owners alone. The higher the rate of land taxation, the greater the proportion of the value created by the community that goes back to the public.

In 1990, a group of 30 economists, including four Nobel laureates (Franco Modigliani, Robert Solow, James Tobin, and William Vickrey), sent an open letter to Mikhail Gorbachev, urging the young Soviet capitalist economy of the “danger” in following the Western developed countries in allowing land rents to be privately collected.

The letter advocated instead for land value taxation — or the “social collection of land rents” — as a stable basis for supporting the new economy.

Support for land value taxation bridges political divides. Milton Friedman famously called LVT the “least bad tax” because the fixed supply of land means that taxes on land don’t create deadweight loss . Usually, raising taxes on the supply of a good or service will discourage production. But since land is fixed, higher taxes do not cause any distortion.

But ideas for how LVT revenues should be used do differ across political perspectives. LVT revenues could replace other tax revenues, reducing or eliminating taxes on both labor and capital. They could be used to offset the costs of large, existing public programs, such as Medicaid or Social Security . Or, they could fund additional public programs, such as public transportation or basic income .

Econometric models predict that replacing some portion of existing taxes with land value taxation would increase GDP (and social welfare).

Some advocates see LVT as a potential source of additional public revenue to be added on top of existing taxes. But even revenue-neutral strategies that simply replace existing taxes with higher land tax rates, raising the same amount of revenue, are predicted to benefit the economy .

One revenue-neutral model of the overall US economy finds that raising the tax rate on land by 5%, and reducing taxes on capital and labor by 28% and 10% respectively, would increase economic output by 15% and social welfare by 3.4% . Going further to replace all current taxes with a 20% LVT and a 12.2% consumption tax would maintain current levels of government revenue while raising economic output by 26% and social welfare by 5.2% .

A revenue-neutral model of the New York City economy that swaps out all its taxes for an equivalent 21.7% LVT is simulated to increase output by 91% and wages by 4%, while decreasing poverty by 34% and land prices by 28% .

Another revenue-neutral simulation that replaces New Hampshire’s statewide property tax with an LVT yielding the same revenue is projected to raise economic output by 0.36% and employment by 0.35% , with these effects expected to persist in the long term .

LVTs would reduce the incentive for land speculation.

Land speculation is an investment strategy where vacant land is bought and held, with no building or development, in the belief that surrounding land values will rise, raising the value of the vacant land, which can later be sold off at a profit. Doing so benefits the landowner while withholding land from development that might benefit the community.

Raising the tax rate on land value would make it more costly to hold vacant land. This would the incentive to speculate without making improvements that generate revenue to offset the taxes.

This projection bears out in both real-world experience and model simulations. When land tax rates were raised in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, the number of vacant lots dropped by 80% . Similarly, the raising of land tax rates in an Australian province led to a decrease in speculation . Along the same lines, simulations for Multnomah County, Oregon, which includes the Portland metropolitan area, suggest that implementing an LVT would reduce land speculation by raising holding costs .

Land value taxation promotes city growth while reducing urban sprawl. But urban development is not without costs, and LVTs may not always be the best tools for promoting development.

LVTs incentivize compact city growth by incentivizing new developments on and around existing developments , which restrains growth from consuming more land. 78% of Americans favor the mitigation of such “urban sprawl” in land use planning.

Evidence from real-world experiments generally supports the assertion that LVTs promote urban development. In Pennsylvania, cities that adopted split-rate LVTs (the form of LVT where tax rates on land are raised while those on capital improvements are lowered, but not eliminated) saw higher levels of construction activity than they would have had they stayed with single-rate property taxes . Similarly, split-rate taxation is shown to increase the number of building permits awarded .

In Pittsburgh, shifting toward higher land taxation led to a 70.4% increase in average annual building permit values. Over the same period, 15 other Eastern cities experienced a 14.4% decrease. The Pittsburgh city council president stated : “I’m not going to say the land tax is the only reason a second renaissance occurred, but it’s been a big help.”

Econometric simulations for both Oregon and New York City also predict that land value taxation would promote development and spur growth.

Depending on context, however land value taxation may not always be a good tool for encouraging development of vacant land, especially in developing countries . Land value taxation is most effective where there is viable, underdeveloped land. In cases where there is little viable land available, however, land value taxation may not be helpful .

In some contexts, land value taxation may prove undesirable. Rapid land development is associated with loss of farmland and open space, higher costs of infrastructure, roadway congestion, and poverty . Land value taxation may also cause over-development. For example, in the 1970s, Hawaii abandoned its land value taxation because it was seen as a cause of overdevelopment in Waikiki .

Land value taxation is highly efficient. Taxing land does not distort its supply in the same way that taxing other goods distorts supply, because the supply of land is fixed. Or, as Milton Friedman put it, land value tax is the “least bad tax.”

Standard economic theory suggests that, when you tax something, supply decreases (since the higher taxes make it more expensive to produce and sell). But because the supply of land is fixed, taxes cannot distort its supply. As a result, land taxes are the most efficient taxes possible.

Even Adam Smith, writing in the 1700s, supported taxing land values . Smith asserted that taxing unimproved land—what he called “ground rent”—would not harm economic activity, would not raise land rents, and would place tax burdens on landowners, who, by definition, monopolize the land .

The appeal of land-value taxation is its basic neutrality: it does not create the adverse fiscal incentives that accompany other revenue measures.

Nonetheless, in theory, there might be certain efficiency concerns surrounding land value taxation. Taxing land values may bias choices between earlier and later development of land in favor of projects that promise earlier revenues to offset the higher taxes. This bias may result in more economically efficient choices being pushed aside to prioritize earlier revenues, leading to less efficient decision-making in land development overall.

In practice, Pittsburgh’s experience suggests that land value taxation offers a unique strategy for municipalities to r aise revenue without resorting to other taxes that may be more likely to distort business decisions.

Evidence from a large natural experiment in Denmark also finds that taxing land doesn’t distort economic decisions , as the tax is fully capitalized into land prices and does not affect user costs of land.

Ultimately, land-based property tax systems...do what they are designed to do—place more of the tax burden on wealthier land-owners, and encourage the highest and best use of land…a LVT would provide a more equitable tax structure, incentivize structure upgrading and development of underutilized properties, and discourage “holding” land for speculative purposes. Furthermore, the potential downsides of the tax policy—such as increasing taxes on low-income homeowners—can be mitigated with carefully crafted legislation.

Effects of Land Value Tax on Stability

Rising housing prices capture much of the gains of economic progress, rewarding the private owners of land with unearned income. Land value taxation would return much of this unearned private capture back to the public that generates it, reducing inequality while improving efficiency.

Land value taxation helps to ensure that those responsible for raising land values share in its financial rewards. It redistributes financial rewards from landowners to communities, and progressively shifts the tax burden onto wealthier landowners and city districts.

Land value taxation can be made even more progressive by using the revenue it raises to finance public programs, such as citizen’s dividends, basic income, or public services like transportation.

According to both theory and real-world evidence, landlords would not be able to pass the tax burden of higher LVTs onto tenants in the form of higher rents.

Rising housing prices are like a sponge that soaks up a significant portion of the gains from economic progress (as economic activity drives up land values), rewarding the private owners of land with unearned income. Land value taxation would return much of this unearned income back to the public who generates it—like wringing the sponge—reducing inequality while improving efficiency.

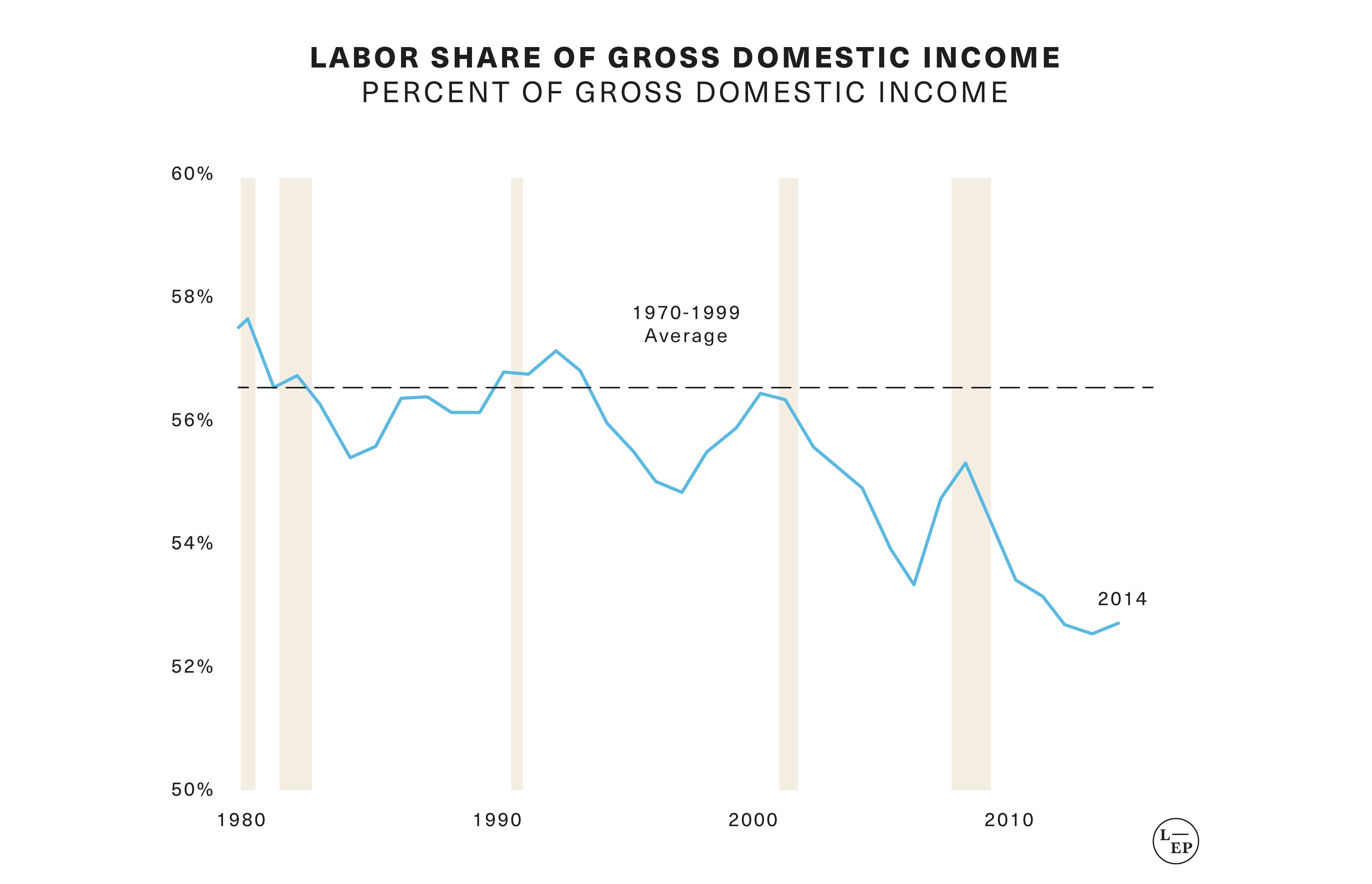

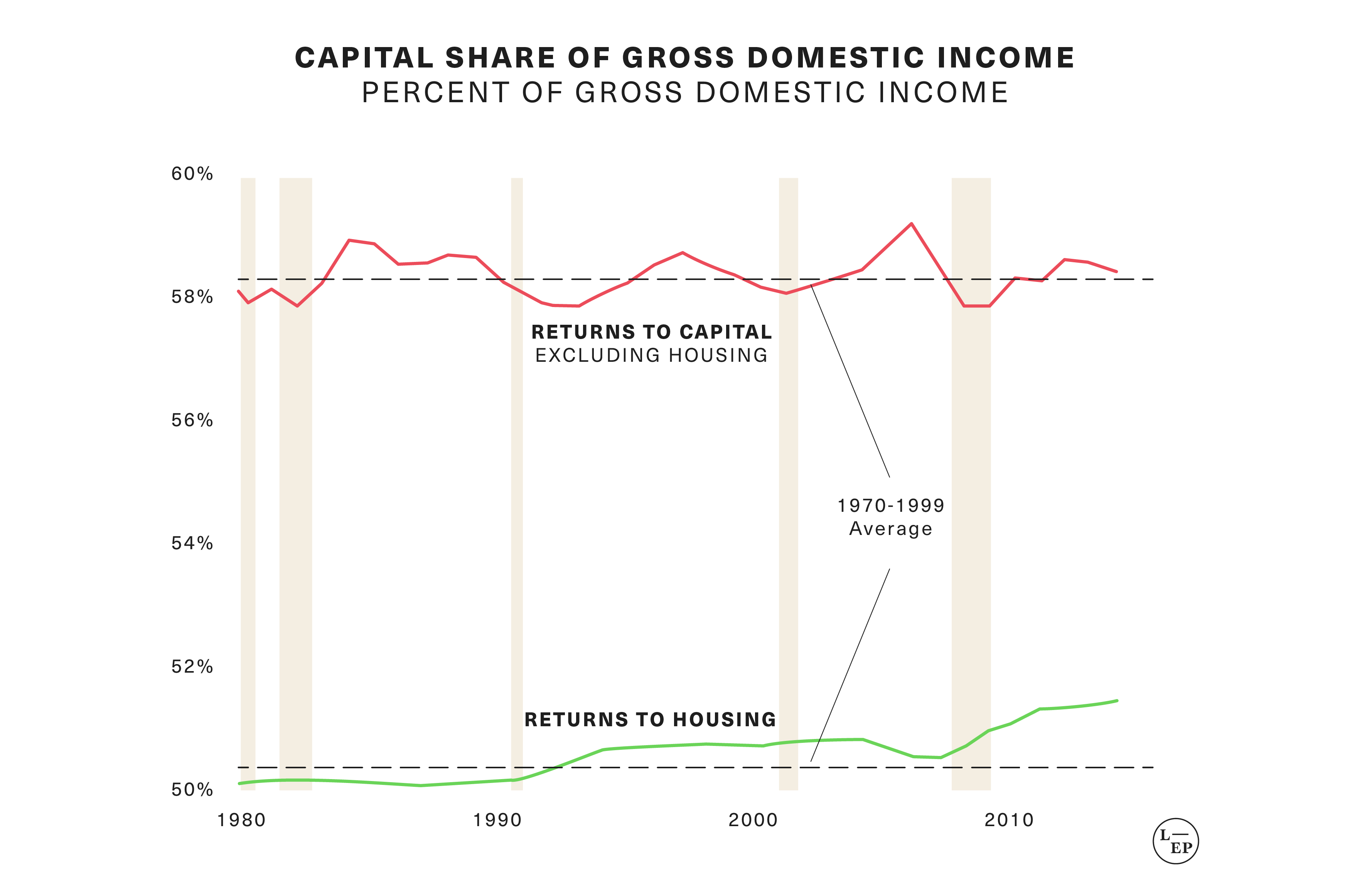

One way to look at inequality is to see how much of the overall national income goes towards laborers (in the form of wages, salaries, and benefits), compared with how much goes towards capital owners (in the form of profits, dividends, and rental income). In recent decades, capital’s share of national income has been rising, while labor’s has declined.

Recent research suggests that the rise in capital’s share is driven entirely by increasing returns on housing . In other words, by private capturing of increases in land values.

By charging higher land rents, property owners privately capture a significant portion of collectively generated economic gains . This reduces economic efficiency because it exercises monopoly power . It also increases inequality by granting unearned income to the already wealthy.

The implementation of LVTs, especially if the revenues were used for public benefit, would divert this captured value from property owners back to the public. Doing so could simultaneously reduce inequality while improving economic efficiency.

Land value taxation helps to ensure that those responsible for raising land values share in its financial rewards. It redistributes financial rewards from landowners to communities, and progressively shifts the tax burden onto wealthier landowners and city districts that benefit from these rising land values in the first place.

LVTs redistribute the unearned gains captured by landlords back to the communities and governments whose activities were largely responsible for driving land prices up in the first place.

They also shift the burden of taxation onto those parts of a city that benefit most from community investments. Such investments range from public sector provisions like transportation and safety to private sector supports like job centers. By shifting tax burdens onto those parts of a city, those who benefit the most from such community investments also contribute more to those investments .

In general, land value taxation makes the overall burden of taxation more progressive. In Oregon, a simulation predicts that implementing a 90/10 LVT (90% tax on land value, 10% on capital improvements) would shift the overall tax burden in Multnomah County from regressive to mildly progressive.

In a simulation for a Texas municipality, replacing the uniform property tax with an LVT would similarly shift the overall burden of taxation from regressive to mildly progressive . Specifically, the burden would shift from single-family residential homes to the commercial and industrial property classes . Over a 10-year period, the LVT would decrease taxes for 85.5% of residential homeowners, and the average single-family property would experience a tax liability decrease of about 30% .

Actual implementation of an LVT in Pennsylvania showed that 85% of homeowners paid less under split-rate land value taxation than they did under uniform property taxation.

There are important exceptions to these trends , however, and land value taxation does not always make the tax burden more progressive. In some cases, where some of the least wealthy may be most likely to face tax increases . These may include farmers who have large plots of land with little development, or more broadly, people who are “land rich but income poor .” Strategies for mitigating such cases are discussed in the Implementation section.

Meanwhile, a study of land value taxation in the UK finds that the tax alone may have a mildly regressive effect, increasing the Gini inequality index by 0.08%.

Land value taxation can be made more progressive by using the revenue it raises to finance public programs such as citizen’s dividends, basic income, or public services like transportation.

To ensure that land value taxation would have a a progressive, equitable outcome that benefits the least well-off, the revenue raised from LVT can be used to fund universal dividends or other public programs.

Conservative estimates of a full LVT (100% tax rate applied to land value) applied across the entire US indicate that its revenues would be enough to provide provide every adult citizen with a citizen’s dividend, or universal basic income (UBI), of roughly $5,750 per year . This would be a financial net benefit to all two-adult households holding property valued at up to $500,000 .

In the UK, a 1% LVT on its own—i.e., without using the revenues to fund additional public programs—would be mildly regressive , raising inequality by 0.08%. But using the increased revenue to fund a UBI would provide a universal payment of £64 per month, reducing poverty by 20% and providing a net benefit to 70% of the population.

A case study of Chicago concluded that land value taxation would be a viable way to finance mass public transportation , while placing the burden of taxation on city areas that benefit most from such public services.

According to both theory and real-world evidence, landlords would not be able to pass the increased tax burden of higher LVTs onto tenants in the form of higher rents.

A common concern with raising taxes on land is that landlords will simply charge tenants higher rents to compensate. But both theory and practice with LVTs find otherwise, alleviating this concern.

With an LVT, the more rent a landlord charges, the more taxes they pay. Because land values are commonly assessed based on the rent that property owners can charge, raising rents causes land values to rise, increasing the landowner’s total tax liability.

In theory, however, some passing of higher tax burdens onto tenants might still occur in places where the updating of land valuation lags behind changes in rent, or where not all land would be covered under the LVT.

Nevertheless, an extensive and growing body of research finds that land rent taxes are fully “capitalized” into land and property prices (meaning the higher tax burden is incorporated into land prices), rather than passed onto tenants as increased rent. The largest real-world experiment took place in Denmark in 2007, where a variety of land tax rates were changed overnight. The resulting increases in land tax owed by landlords were fully capitalized into land prices, rather than passed onto tenants .

A study of 675 German municipalities finds the same - land taxes are absorbed into land values, rather than rent rates.

In an Australian territory, raising LVT rates saved the typical new home buyer between $1,000 and $2,200 on mortgage payments .

Implementation

Despite high theoretical appeal and some real-world success stories, land value taxation is seldom implemented. Difficulties with the valuation and revaluation of land and educating taxpayers, along with patchwork data collection practices and general bureaucratic friction, have all contributed to obstructing implementation.

Although measuring the value of land separately from capital improvements is difficult and prone to measurement error, it is far from insurmountable. New statistical methods of land appraisal may ease these burdens.

The implementation of LVTs would be complemented by the repealing of restrictive zoning policies. Restrictive zoning policies inhibit the potential benefits of land value taxation. At the same time, LVTs would raise incentives to repeal such zoning policies, possibly making such repeals easier to achieve.

Although switching to LVTs would be progressive overall, it would place undue tax burdens on certain demographics, such as ‘land rich, income poor’ people and on farms. Strategies to mitigate these burdens include gradual implementation of LVT rates, grandfathering in existing households under previous arrangements until death or until sale of property, exemptions, and direct relief.

LVTs were originally proposed as a “single tax” at a rate of nearly 100% of land value. In practice, however, the high end of rates in recent LVT implementations have only reached 39.6% in Altoona City, Pennsylvania (where the LVT was later repealed). At the national level, recent estimates suggest that an LVT rate of 5.55% would be politically viable and would increase economic output and social welfare, but a 20% rate would be optimal.

Despite high theoretical appeal and some real-world success stories, land value taxation is seldom implemented. Difficulties with the valuation and revaluation of land and educating taxpayers, along with patchwork data collection practices and general bureaucratic friction, have all contributed to obstructing implementation.

A successful LVT depends on the administrative capacity to assess the value of land separate from the value of any buildings or improvements on the land. As it turns out, this is rather difficult to do when existing data collection practices have not been designed for it. These administrative obstacles, plus political factors, have generally been sufficient to discourage the implementation of land value taxation despite its strong theoretical appeal.

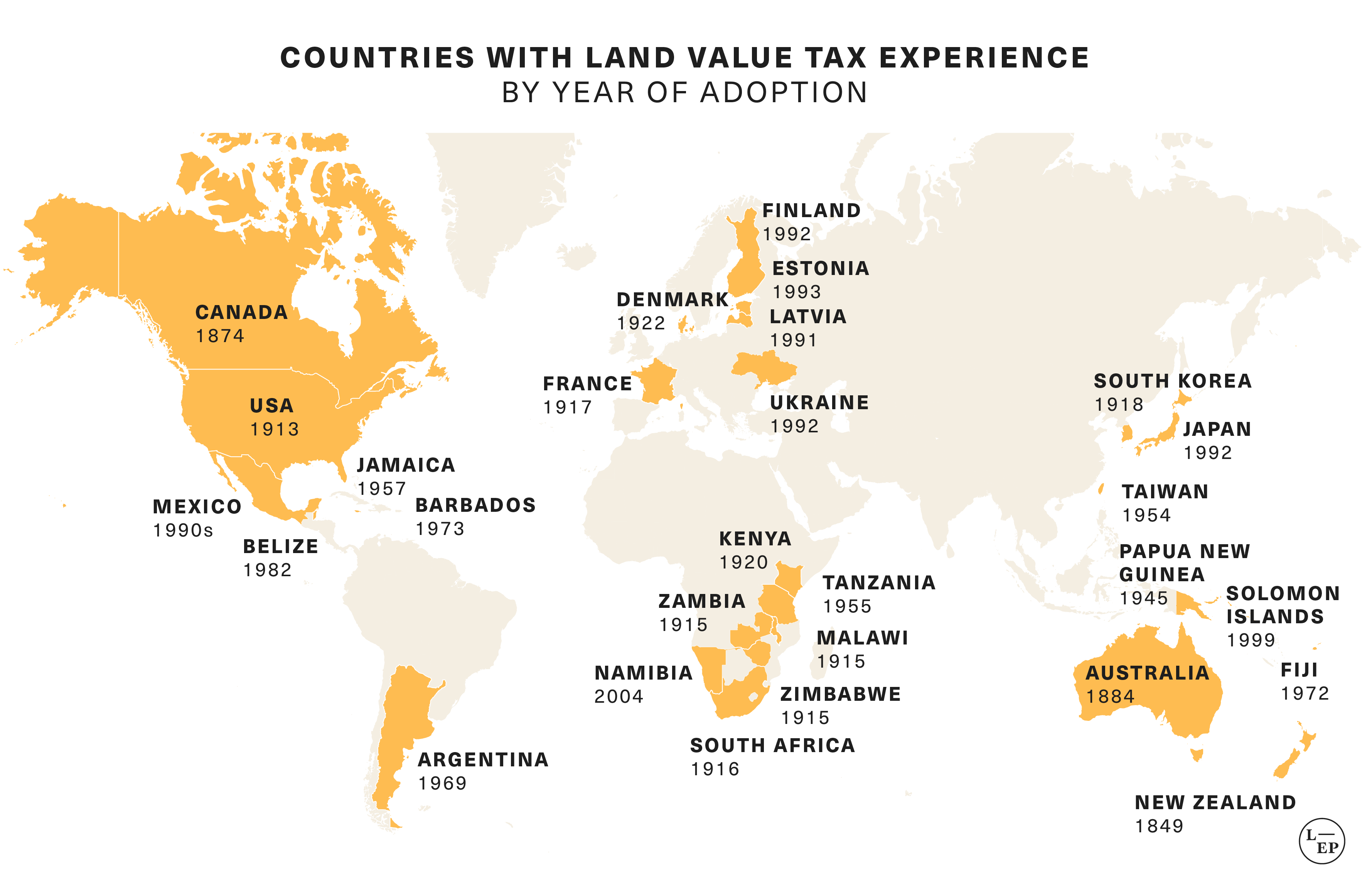

Various forms of land value taxation either were or currently are practiced in parts of Denmark, Australia, Estonia, Pennsylvania, Hong Kong, Hungary, Kenya, Mexico, Namibia, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand.

In Altoona, Pennsylvania, an LVT was implemented for a number of years in the 2000s and 2010s, but ultimately abandoned due to ineffectiveness and general confusion. In Pittsburgh, a nearly century-long practice of split-rate land value taxation was repealed due to poor assessment practices , despite evidence that it encouraged building activity.

In Minnesota, county and city assessors are skeptical of transitioning to even a moderate form of land value taxation. Only 9% believed land value taxation was an idea worth pursuing, and 40% strongly opposed .

In Australia, inconsistency and lack of transparency in land valuation methods has led to their LVT to becoming one of the more disliked and least understood taxes .

The technical difficulty of how to value unimproved land, while not insurmountable, is considerable and prone to generating confusion and a lack of transparency. There needs to be a good understanding regarding what LVT is and what it is supposed to achieve and sufficient resource put behind the valuation exercise.

As such, a case study for implementing land value taxation in Washington DC comments that any reallocation of valuation between land and improvements would require resources to be earmarked for taxpayer education.

But perhaps the one of the most well-credentialed assessments of the administrative barriers to implementing land value taxation comes from the above-mentioned open letter to Mikhail Gorbachev. Written in 1990, well before we had the statistical methods and digitized data practices we have today (which offer new, simpler ways of assessing land value), the group of 30 economists, including four Nobel Laureates, noted the technical issues impeding land value taxation, and wrote : ”While these issues need to be addressed, none of them present any insoluble problems.”

Measuring the value of land by itself, separate from buildings and improvements, is difficult and prone to measurement error, but far from insurmountable. New statistical methods of land appraisal may ease these burdens.

Land valuation is tricky, and increasing the tax burden on land would increase the importance of land valuation practices.

Current methods for distinguishing land value from property value are prone to error . But even so, it is important to keep in mind that land value taxes are found, at worst, to carry distortion effects equivalent to those of current property tax practices , even when higher ranges of potential error are taken into account. The majority of complaints today about property value assessments take issue with the value of buildings and improvements, not land value.

There have long been methods of determining land value “by hand,” reaching as far back as a short-lived LVT implemented by Houston’s first Hispanic mayor, J. J. Pasoriza , in 1911. But newly developing statistical methods are already found to be cheaper, faster, and no less accurate than conventional property assessment methods .

New methods of land valuation are diverse , ranging from various forms of regression analysis, to machine learning algorithms and neural networks.

The implementation of LVTs would be complemented by the repealing of restrictive zoning policies. Restrictive zoning policies inhibit the potential benefits of land value taxation. At the same time, LVTs would raise incentives to repeal such zoning policies, possibly leading more easily to such repeal.

In areas where zoning laws prevent urban development and densification, an LVT may have limited effect . For example, in Washington DC, a primary barrier to residential densification is the large number of lots (95,835) zoned for single-family residential housing , of which 71% face significant zoning barriers to densification.

If an LVT were in place, its effects on development would be significantly limited by such zoning barriers. But land value taxation raises incentives to maximize land value (which also maximizes the tax base for the city). Because land values are depressed by restrictive zoning practices, the implementation of land value taxation would rase the opportunity cost (i.e., increase the sacrifices) of maintaining such practices. Thus, passing an LVT could strengthen the case to repeal restrictive zoning ; in return, the repealing of restrictive zoning could help realize the full effects of an LVT.

Additional zoning reforms to complement land value taxation could include supporting the development of Accessory Dwelling Units and expanding mixed-use zoning .

Although switching to LVTs would be progressive overall, it would place undue tax burdens on certain demographics, such as “land rich, income poor” people and on farms. Strategies to mitigate these burdens include gradual implementation of LVT rates, grandfathering in existing households under previous arrangements until death or until sale of property, exemptions, and direct relief.

Overall, an LVT in the US would decrease tax payments for most residential properties , shifting the burden onto wealthier landowners and the commercial or industrial property classes .

There are important exceptions, however, in which an LVT might cause some of the least wealthy to be most likely to face tax increases . In particular, “ land rich, income poor” groups , such as farmers or long-time residents, may face higher tax burdens.

In most cases, these undue tax burdens are one-time scenarios , experienced only by the owner at the time of the tax change. For future owners, the higher rates are factored into the land’s price.

These obstacles can be remedied. Strategies to mitigate them include exempting specific types of land (as Estonia does with nature reserves and public water bodies, or Australia does for agriculture ), grandfathering in long-term residents until death or until sale of property , gradually phasing in the LVT rate rather than allowing it to cause a sudden rate spike, or direct relief .

LVTs were originally proposed as a “single tax” at a rate of nearly 100% of land value. In practice, however, the high end of recent LVT implementations have only reached 39.6%—in Altoona City, Pennsylvania (where the LVT was later repealed). At the national level, recent estimates suggest that an LVT rate of 5.55% would be politically viable and would increase economic output and social welfare, but a 20% rate would be optimal.

When first proposed by the American economist Henry George, land value taxation was proposed as a “single tax” at a rate of nearly 100% of land value that would replace all other taxation. The tax landscape of the 1800s was significantly different from today’s , however, and the benefits of land value taxation remain even if an LVT would not replace all other taxation.

A 2019 estimate (using simplified assumptions) projected that a national 100% LVT would raise anywhere from $1.1 trillion to $3.36 trillion per year , or between 25% and 76% of total government spending. But in practice, in American cities where LVT has been tried, land value taxation has generally remained revenue-neutral, only raising rates on land high enough to offset decreases in taxes elsewhere.

In New York City, one estimate found that a revenue-neutral LVT that replaced all income, property, and corporate taxes would need to be set at 21.6% to maintain levels of revenue. Across jurisdictions in Pennsylvania that used split-rate LVTs in 2013, tax rates on land ranged from 0.4% in the Pittsburgh Business District to 36.9% in Altoona City. During Pittsburgh’s use of a split-rate LVT from 1913 to 2001, the tax on land was roughly 5.77 times that on improvements.

Where a national LVT is concerned, a recent comprehensive study suggests that land value taxation offers a promising path forward for financing current levels of expenditure and debt, while decreasing tax rates on both capital and labor. Specifically, it finds that the marginal benefits per 1% increase in land tax rates remain large until the rate reaches around 10%, after which the predicted gains in economic output and social welfare taper off.

Their suggestion for short-term action is to raise the current tax rate on the asset value of land from 0.55% to 5.55%, allowing for a revenue-neutral decrease in taxes on capital by 28% and labor by 10%. Doing so, their model predicts, would raise welfare by 3.4%, and increase output by 15%.

In the study’s optimal model, all current tax revenue could be replaced by a 20% land value tax and a 12.2% consumption tax. Doing so would increase social welfare by 5.2% and economic output by 26% .

Land value taxation could come “from above,” as a federal mandate, or “from below,” since any municipality could implement an LVT on their own.

Globally, LVTs have been implemented as booth local and national policies. Denmark , Finland , Estonia , and Taiwan offer examples of national LVTs “from above.” In Taiwan, LVT revenue accounts for 8.4% of total government revenue.

A strong example of land value taxation “from below” can be found in the US, in Pennsylvania, where the city of Harrisburg’s experience offers an especially positive example . After land value taxation was implemented in 1975, Harrisburg’s tax base rose from $212 million to $1.6 billion, the number of vacant lots feel by 80%, crime fell by 46%, over 40,000 new building permits were issued , and the number of residential units significantly increased.

In contrast, the Pennsylvanian city of Altoona adopted a LVT in 2002, but repealed it in 2016 following general confusion and the LVT’s relative inefficiency.

With land value taxation, as with all policy design, the details are crucial.